iphoneography showing summer 2014 in idaho

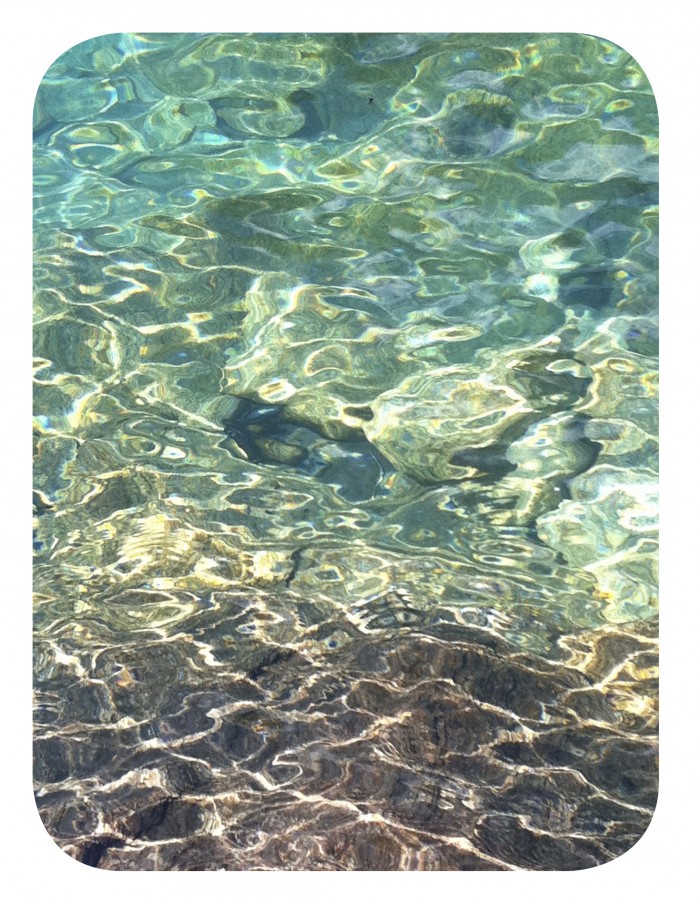

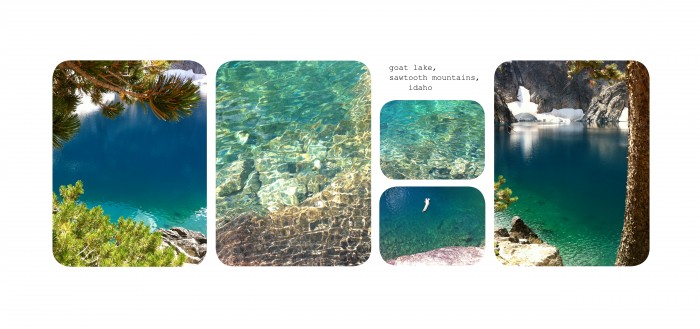

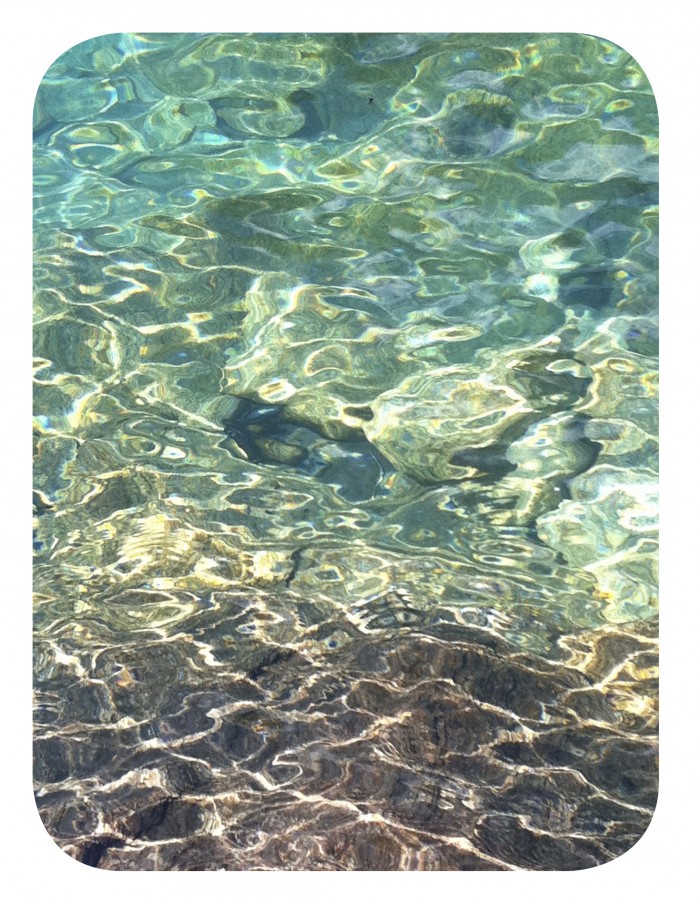

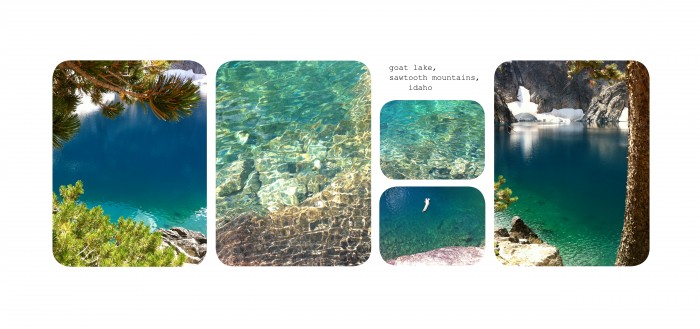

goat lake, sawtooth mountains, idaho

goat lake, sawtooth mountains, idaho  (showing all summer 2014 at Redfish Lake Visitor’s Center)

(showing all summer 2014 at Redfish Lake Visitor’s Center)

goat lake, sawtooth mountains, idaho

goat lake, sawtooth mountains, idaho  (showing all summer 2014 at Redfish Lake Visitor’s Center)

(showing all summer 2014 at Redfish Lake Visitor’s Center)

Ecobuddhism: How do you feel about the Sixth Mass Extinction?

Joanna Macy: It’s happening. It’s combined with so much else that promises wholesale collapse. How do we begin to deal with the plastic in the ocean that covers areas the size of countries? What are cell phones and microwaves doing to our biological rhythms? What exactly is in our food? How do we address genetic modification of crops? We are so hooked on all of this, on every level. How do we begin to contain it?

The most immediate level of crisis concerns the Earth’s carrying capacity. Many civilizations prior to ours, starting with Mesopotamia, could no longer support themselves because they exhausted their natural resources. Carrying capacity is the level most people talk about. It’s a defining aspect of the climate crisis. How will we grow the food we need given huge variations and extremities of weather? How will we handle the natural disasters and famines that will result from a chaotic climate?

The second and deeper level is that consequences will extend far beyond the collapse of this civilization. We are creating a lack of possibility for future generations and civilizations, because we are using up mineral and petroleum resources without a thought for them. When this civilization collapses, the future will have largely Stone Age possibilities.

The third level of crisis is the enormous increase in the rate of extinctions—shredding the fabric of life, creating a loss of biodiversity so extreme that we can glimpse the doom of complex life forms. It takes highly differentiated and integrated and diverse systems to produce life forms complex enough for consciousness.

The fourth level of crisis would be the destruction of everything more complex than anaeorobic life forms, because of the loss of our oxygen production in the oceans and on land.

At any rate, I take all of these crises seriously and don’t argue with them. At the same time, I spend my life and breath to open our minds, and to change our heart-minds.

Sunsets are beautiful too, not just sunrises

EB: From where do you derive the psychic resources to bear witness to all this, while keeping in touch with joy?

JM: There’s a lot of joy in it. I find myself very buoyed by the work I do. I call it the work that re-connects. It involves speaking the truth about what we are facing. I think it’s very hard for people to do that alone, so this work thrives and requires groups.

It needs to be done in groups so we can hear it from each other. Then you realize that it gives a lie to the isolation we have been conditioned to experience in recent centuries, and especially by this hyper-individualist consumer society. People can graduate from their sense of isolation, into a realization of their inter-existence with all.

Yes, it looks bleak. But you are still alive now. You are alive with all the others, in this present moment. And because the truth is speaking in the work, it unlocks the heart. And there’s such a feeling and experience of adventure. It’s like a trumpet call to a great adventure. In all great adventures there comes a time when the little band of heroes feels totally outnumbered and bleak, like Frodo in Lord of the Rings or Pilgrim in Pilgrim’s Progress. You learn to say “It looks bleak. Big deal, it looks bleak.”

Our little minds think it must be over, but the very fact that we are seeing it is enlivening. And we know we can’t possibly see the whole thing, because we are just one part of a vast interdependent whole–one cell in a larger body. So we don’t take our own perceptions as the ultimate. My world view has been so interwoven between the Buddhist teachings and living systems theory. They inform each other so powerfully.

“Beings are numberless, I vow to liberate them all”. This may be the last gasp of life on Earth, and what a great last gasp, if we realize we have fallen in love with each other. If you are really in the moment of experiencing our reality, you don’t say “Oh I won’t experience this because it’s not going to last forever!” You’ve got this moment. It’s true for now. We can have a reasoned concern about what is down the track, without necessarily getting hooked on something having to endure.

EB: Even in Buddhism, where impermanence is a matter of course, there are no obvious concepts to deal with super-impermanence, in the sense that humans are now bringing an end to the Cenozoic era. In the best case, there may be an Ecozoic era to follow it. Continuing on our “business-as-usual” trajectory will acidify the oceans and trigger runaway global heating, epic mass extinction and a completely new cycle of geological time. A few climate scientists consider we may have already entered into runaway climate change.

JM: I suspect that they are right. Logically they are right: we don’t have a snowball’s chance in hell. At my last workshop, people were saying “It’s too late” in the Truth Mandala that we do. And then they went out and got arrested at the White House, chained to the fence to protest the wars. So our acting with passionate dedication to life doesn’t seem to be affected. I would just as soon live that way. What keeps you going? Are you not fed by your work?

EB: Yes, it’s a powerful personal evolutionary demand that has to be lived. There is no choice.

JM: How lucky we are to be alive now—that we can measure up in this way.

EB: In the film about Jung’s life, A Matter of Heart, Marie-Louise van Franz reveals some visions he had towards the end of his life, where a large part of the planet was destroyed, but a small part endured.

JM: Certain Tibetan predictions and prophecies also indicate there will not be a total extinction of humans.

EB: James Lovelock asserts that America and China will continue to use fossil fuels and compete for the last resources till it is too late. Civilization and most of the great ecosystems will collapse. A human population of a few million might survive around the Arctic Circle.

JM: These are what the Buddha would call “views”. They are based on a lot of scientific evidence, so I take them very seriously. But what it comes down to is that we are here now. So the choice is how to live now. With the little time left, we could wake up more. We could allow this whole experience of the planet, which is intrinsically rewarding, to manifest through our heart-minds—so that the planet may see itself, so that life may see itself. And we can bless it in some way. So there is some source of blessing on us, even as we die. I think of a Korean monk who said “Sunsets are beautiful too, not just sunrises.” We can do it beautifully. If we are going to go out, then we can do it with some nobility, generosity and beauty, so we do not fall into shock and fear.

The work that I do we call The Work that Reconnects. I sensed from the time that I started it a little over 30 years ago, that on one level it was to help people be better activists – more resilient, more creative, more responsible, more effective. And on a more ultimate level, I recognized I was doing it so that when things fall apart, we won’t turn on each other.

EB: Lovelock considers humanity could become a disorganized rabble led by competing war lords.

JM: That is already happening! Look at America. We are at each other’s throat. We are steeped in delusion and lies.

EB: And that could well be a strategy of Disaster Capitalism. Perhaps a transpersonal movement in the collective unconscious could bring about a social tipping point.

JM: Or even in the collective consciousness. We can never say from our little point of view that it’s too late for that.

The Privatization of Practice

EB: In The Corporation, Joel Bakan asked a leading psychiatrist to examine corporate behaviour (externalizing all costs onto society) using standard diagnostic criteria. The doctor found he was looking at the profile of a psychopath. The dominant institution of our time has been created in the image of a psychopath, and it is legally mandated to behave as such.

JM: That’s right, they are required to! And no system where you try to maximize just one variable can avoid runaway. Indeed the bad news has gotten overwhelmingly bad since a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court gave corporations the right to make unlimited, secret political donations in Citizens United vs the FEC.

EB: We have a conjunction of “corporate psychopathy” with the immense power of fossil fuels–the most profitable business in human history. And though it’s potentially fatal for our species, it’s so difficult to hear the story. The American broadcast media is thoroughly controlled by corporate ownership or advertising revenue.

JM: They have reduced the population to a state of such stupidity. I don’t even watch TV. I suppose I should, if only to see what is happening to my country. It’s a terrible degeneration, a cultural nausea. Even listener-supported radio, which provides some oxygen, is under assault. In America now we live in a “national security state” with a debilitating element of mental servitude or mind control.

And as far as Buddhism is concerned, I find that Western Buddhists tend to privatize their practice, and look for what I call premature equanimity. They go for peace of mind and that is such an inadequate response.

EB: Spiritual practice as anaesthetic? If we can put a name to certain things, there’s a possibility of opening new space up for spiritual creativity. Just as the Australian Zen teacher Susan Murphy named something important when she wrote about The Untellable Non-story of Global Warming. Every week Australian farmers commit suicide because their land and their lives have been completely ruined by drought, while large mining corporations corrupt its politics and export its coal to heat China’s blast furnaces.

Uncertainty, Despair & Positive Disintegration

JM: I find a lot of what I am drawn to in the teaching I do, the experiential work, is to help people make friends with uncertainty, and reframe it as a way of coming alive. Because there are never any guarantees at any point in life. Perhaps it’s more engrained in the American citizen that we feel we ought to know, we ought to be certain, we ought to be in control, we ought to be upbeat, we ought to be smiling, we ought to be sociable. That cultural cast has tremendous power to keep us benumbed and becalmed. So it’s been central to my life and my work to make friends with our despair, to make friends with our pain for the world. And thereby to dignify it and honour it. That is very freeing for people.

EB: I suppose it is to embrace the shadow as well.

JM: Yes, and it’s a big shadow. I find certain science fiction, the imagination, very helpful here. I like to be stretched. Olaf Stapledon wrote in the 1930s, before the nuclear age, with an incredible imagination that was also profoundly spiritual. In The Star Maker, the human mind of Earth in the head of a particular man starts to voyage through space/time and sees the drama that we are involved in here, recognizing our mutual belonging before we kill each other. He sees this basic drama in many different forms, and it’s so rich. Of course, there are planets where consciousness came that just failed. But the adventure as a whole is so big.

Living systems theory has been so helpful to me. I think there is a drive within living systems to complexify, to wake up—there is an evolutionary movement. I speak out of the love and excitement generated by my little work, which many people are doing with me. It does require being able to experience pain. It does require tears and outrage. It does require positive disintegration. Our whole culture needs positive disintegration. It has to die to itself. So my Christian upbringing is relevant there: Good Friday and Easter, the necessity for death and rebirth. We are going to die as a culture, and it’s better for us to do it consciously, so we don’t inflict it on everyone else.

The Death Wish & the Fourth Gem

EB: Are we going to die as a species too? Would the ego-death of our species precede or modify an extinction of our species?

JM: Well, I suppose one could make a deep ecology/activist case for a species-specific poison to be put into the system, to get rid of the humans for the sake of non-humans. But it’s too late for that because we have poisoned the planet with our radioactive materials and all our other toxins. Only we can know what they are, so we need to stay around to keep them out of the biosphere to the extent that we can. We don’t have the luxury of committing suicide as a species.

EB: Yet the famous evolutionary biologist Edward Wilson wrote that remarkable article, Is Humanity Suicidal?

JM: Well we are acting that way. We are acting as if we had a colossal death wish.

EB: Your workshops are obviously coming from the experiential side. If we look at Eco-psychology, all that Rozsak and colleagues have done, I wonder if there is a case to develop a certified practical training. Would that be useful?

JM: Oh my goodness, yes. But the academic institutions are not friendly to something that eludes the control of narrowly-defined disciplines. So there are probably some other places you can go.

Wherever I go with workshops, I find the readiness to experience a collective awakening. I’m astonished by how explicit this is. It’s a sense of wanting to belong to the Earth, aching for reverence for the Earth. Again and again, I believe that people would be ready to die for our world, to save the life process. There is something pressing within the heart-mind that is just huge. It’s happening very fast.

That’s one nice thing about being as old as I am. I am 81 and I’ve been watching the mindset of people through the 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s and the first decade of this century. I was doing doctoral work as late as the 70s. The changes since then are staggering.

A major change is the relevance people are now finding in native American teachings. There’s a deep respect for the wisdom that is there, and for the nobility of character that it fostered. I think that it is a precious addition to our triple gem—this fourth gem of our time—that the native peoples are speaking out.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Eco-philosopher Joanna Macy (b 1929) is a scholar of Buddhism, general systems theory & deep ecology. A respected voice in movements for peace, justice, and ecology, she interweaves her scholarship with four decades of activism. She has created a ground-breaking theoretical framework for personal & social change, as well as a powerful workshop methodology for its application. Her wide-ranging work addresses psychological and spiritual issues of the nuclear age, the cultivation of ecological awareness & the fruitful resonance between Buddhist thought and contemporary science. The many dimensions of this work are explored in her 10 books. Many thousands of people around the world have participated in her workshops, which help people transform despair and apathy, in the face of overwhelming social and ecological crises, into constructive and collaborative action. They elicit a new way of seeing the world as our larger living body, that frees us from the assumptions and attitudes that now threaten the continuity of life on Earth. Joanna travels widely giving lectures, workshops & trainings in the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Australia. She lives in Berkeley, California, near her children and grandchildren.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

from—

http://www.ecobuddhism.org/wisdom/interviews/jmacy